As the founder of the Nguyen dynasty, travellers might expect Emperor Gia Long’s tomb to be something of a Hue showpiece. The guy’s a giant in Vietnamese history. But Vietnam’s official ambivalence towards its regal past is perfectly illustrated by the rundown state of the burial place of the man who made Hue the capital of united Vietnam in 1802. I couldn't find a single mention of his name, or a word about his life, at the site.

That same ambivalence is presumably what makes Hue a confusing heritage-without-history, travel destination.

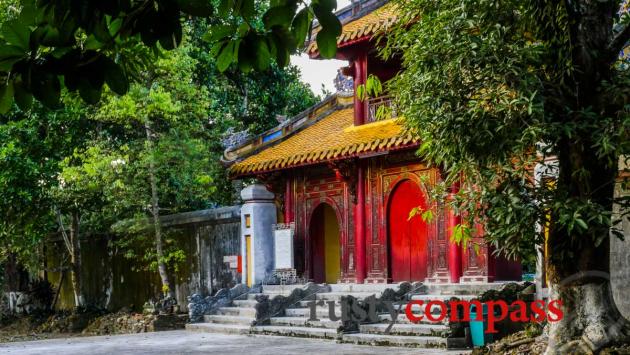

Gia Long’s Tomb is located 18km from Hue making it the most distant of the major tombs. It’s a sprawling, serene complex set in picturesque hill country. The journey to the tomb is a big part of its appeal.

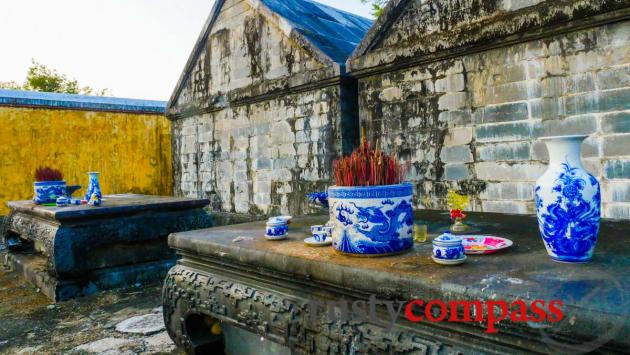

While few of the original structures remain, Gia Long’s sarcophagus, with his wife beside him, survived the Vietnam War era battles that destroyed other structures here.

On both visits I've made, a friendly security guard held the key to the courtyard where the tombs lie. Most recently, he asked for 100K VND to open the large door. I obliged hoping that some of that money might contribute to the upkeep of the site. He told me a paltry 20 tourists had visited that day.

It was Gia Long that built the Imperial Citadel and it was this tomb that set the precedent of extravagant burial monuments that Gia Long’s successors followed. Odd then that many a traveller might pass through Hue without even knowing the man’s name let alone his accomplishments.

Background

In the midst of the fierce fighting of Vietnam’s Tay Son rebellion in the late 18th century, a young Nguyen lord named Nguyen Anh (later to become Gia Long) was forced into hiding. He took refuge on modern day Phu Quoc Island and in the Mekong Delta town of Ha Tien among other places.

By the late 18th century, Nguyen Anh had set about putting down the Tay Son rebellion and conquering Vietnam in his family’s name. The Nguyen clan had ruled southern and central Vietnam for two centuries prior to the Tay Son uprising.

During his time in hiding, Nguyen Anh made the acquaintance of French missionary, Pigneau de Behaine who saw political manoeuvring as a valuable tool in his missionary work. Behaine made overtures to Paris in support of Nguyen Anh’s campaign and when French military assistance was withheld, set about assembling an assistance force himself.

While Behaine’s support was not decisive in Nguyen Anh’s victory, it has stained the king in Vietnamese history as a collaborator with the French. His relations with France established an unhappy precedent that would blight his successors when France decided to deepen its claim on the country.

That Nguyen Anh’s main adversary in the Tay Son rebellion was Nguyen Hue, one of Vietnam’s most celebrated national heroes, has further tainted his legacy. While national leaders to this day, flock to the Nguyen Hue (aka Quang Trung) Museum outside of Quy Nhon, Gia Long enjoys no such prestige.

If time permits, Gia Long’s tomb is worth visiting - in equal parts for the journey, the setting and the curious national outcast who is remembered here.

Travel tips

A new makeshift bridge across the Perfume River means that a boat ride is no longer required to get to Gia Long’s tomb. The bridge isn’t suitable for cars however. The energetic will find this an enjoyable cycling trip (once out of Hue) and it’s also comfortably done by motorbike or xe om motorcycle taxi. Navigation can be an issue. Follow the river road past Khai Dinh’s Tomb and then follow the signs. It’s also possible to reach the tomb on a long river trip from Hue that could also include Minh Mang’s tomb. Taking a motorcycle taxi will minimise the risk of getting lost. Don’t expect to see too many other travellers.

There are no comments yet.